Correlation vs. Causation — How to respond to a buzzword bomber

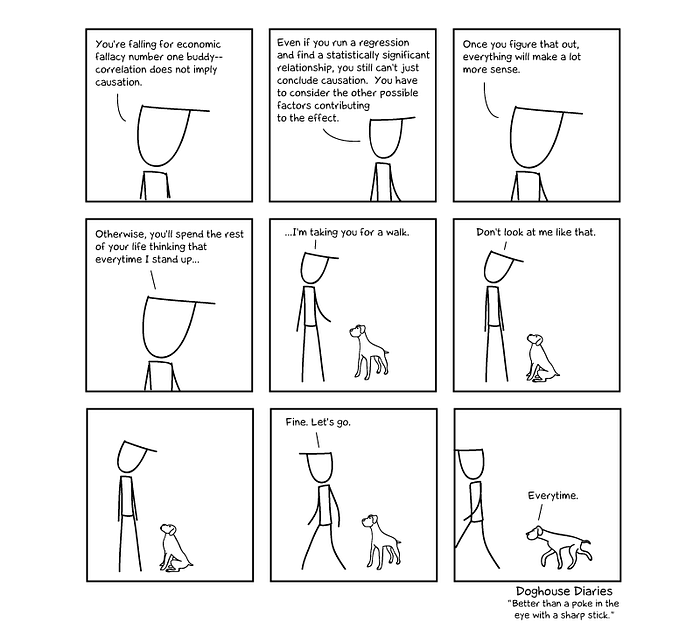

Correlation is not causation. It is common knowledge; thanks to the constant supply of social media feeds.

For example, for sure, you could test your 5-year old next time you are in a plane whether he has it figured out like Family Circus: I wish they didn’t turn on the seatbelt sign so much! Every time they do, the airplane gets bumpy.”

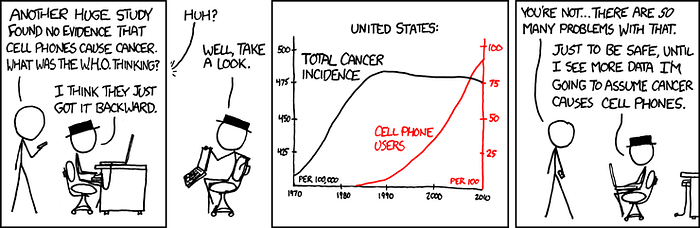

Here is a relationship between cell phone and cancer uses.

As a tech employee for a large organization, we often deal with buzzword bombers who overdo correlation vs. causation; they throw it specifically at the analysis that is contradictory to their agendas. Personal preference and biases blind, even the best. Fisher, a smoker, dismissed the body of work that proved smoking caused cancer for decades on account of ‘correlation vs. causation’.

No wonder, in a matrix organization, we meet a lot of leaders, guided by their agenda, slander a reasonably solid analysis quipping,” correlation is not causation.”

Proving smoking caused cancer was tough because the opponents were two behemoths: billion-dollar Tobacco companies and Fisher. We are not in a pickle because 1. Fisher is not our opponent 2. Fisher, along with other philosophers are on our side 3. the force of billion-dollar is not working against us.

“Cause and Effect” have puzzled philosophers for centuries, and they came up with below five broad definitions:

- Primitive definition of willful force: Someone did something with the intent of producing an effect. For example, a caveman kills an animal with a spear. The will of the cavemen has caused the death of the animal. Conspiracy theorists make use of this definition. Politicians, bankers, and foreign countries cause such and such event. For complicated cases like smoking, it doesn’t work.

- Koch’s definition: It’s a comprehensive definition but it holds only for bacterial or viral infection. The virus is injected, and it causes infection. A sample from infection is taken, and we can cultivate the virus. The cultivated virus is injected into a new sample, and it causes the disease. This “cause and effect” works only for simple cases, and doesn’t work where the same disease can happen because of other factors as well.

- Randomized controlled experiments: Fisher himself came up with a definition of cause and effect. He said it works only for planned experiments. It is called inductive reasoning.

- Material definition from symbolic logic: An event A implies an event B if it is not possible for B to occur when A has not happened. It is a simplistic definition and is not exhaustive at all. We can’t even say that the caveman from ‘primitive definition’ has caused the death of the animal. The animal could die of other causes as well.

- Cause can’t be defined: Bertrand Russel called the discussion of “Cause and Effect” a silly superstition. It is in line with David Humes’s idea that “Cause and Effect” can not be defined.

Closing thoughts

Correlation is well defined, but “cause and effect” are not. We can’t define ‘cause,’ so we can never be sure of the cause. “Cause and Effect” is a silly superstition.

Yet, we can’t stop making decisions because we are not certain. We should go ahead with restrictive definitions:

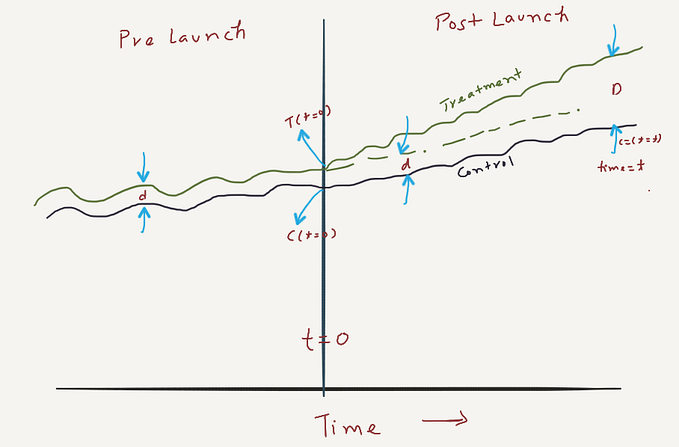

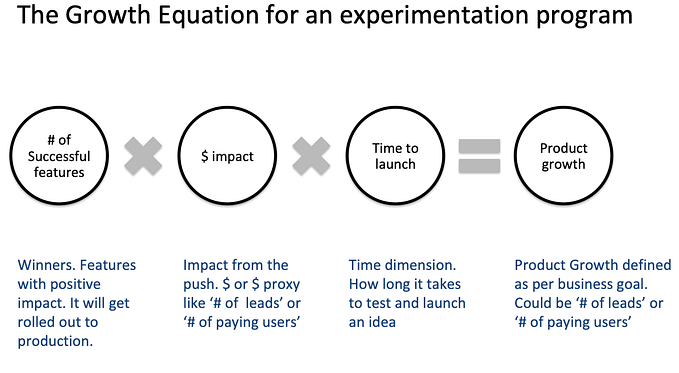

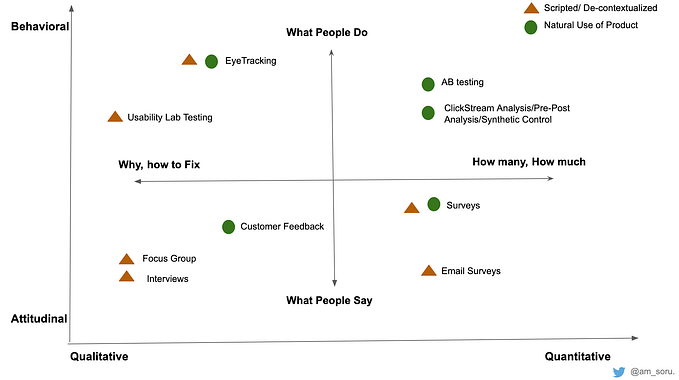

For a randomized experiment, if the numbers are significant, and it aligns with the growth model of your business, please be confident in your work. It is as good a causal relationship you will see in real life.

For cases where you don’t have a randomized control, you have to go ahead with your understanding of the business as per the growth model. If it aligns with the growth model then it is causal.

If you have peers throwing ”correlation is not causation” bomb, please let her know that ‘cause’ can’t be defined. If she still insists, tell her the story of Fisher and forward this blog.

Reference and Further Reading:

Causal inference in statistics